Select a brand to scroll through the lab tests

Why should you be concerned with your kratom being lab tested?

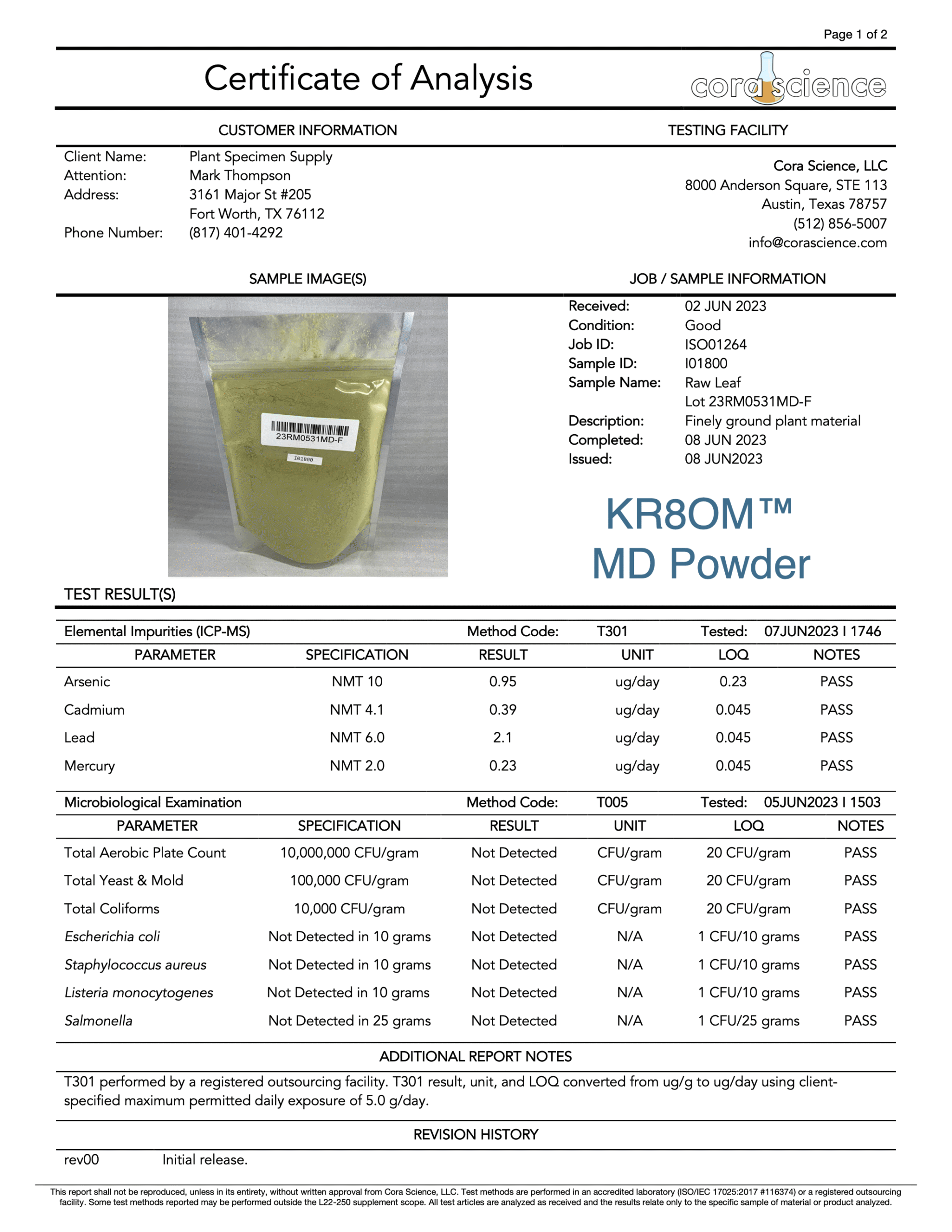

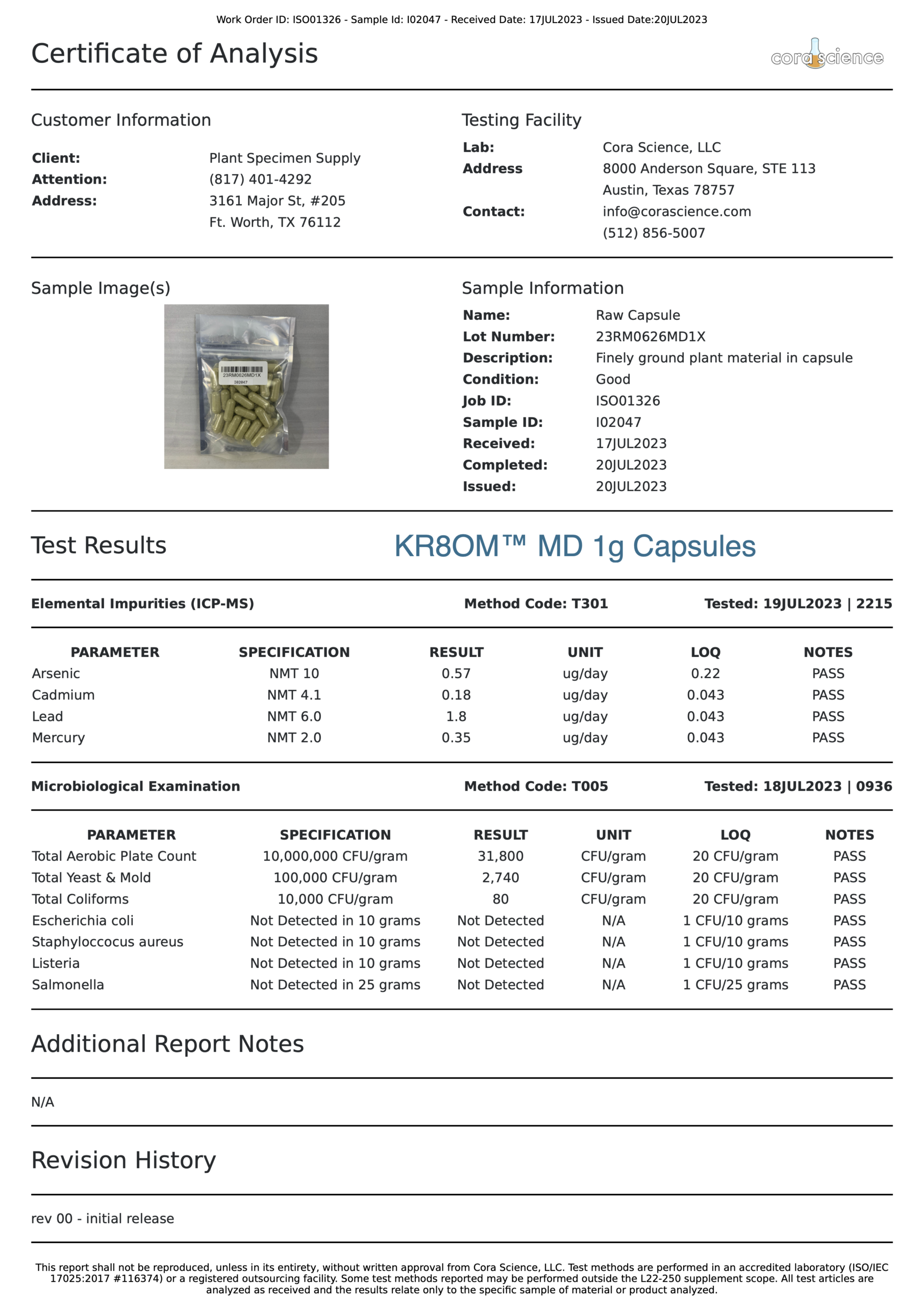

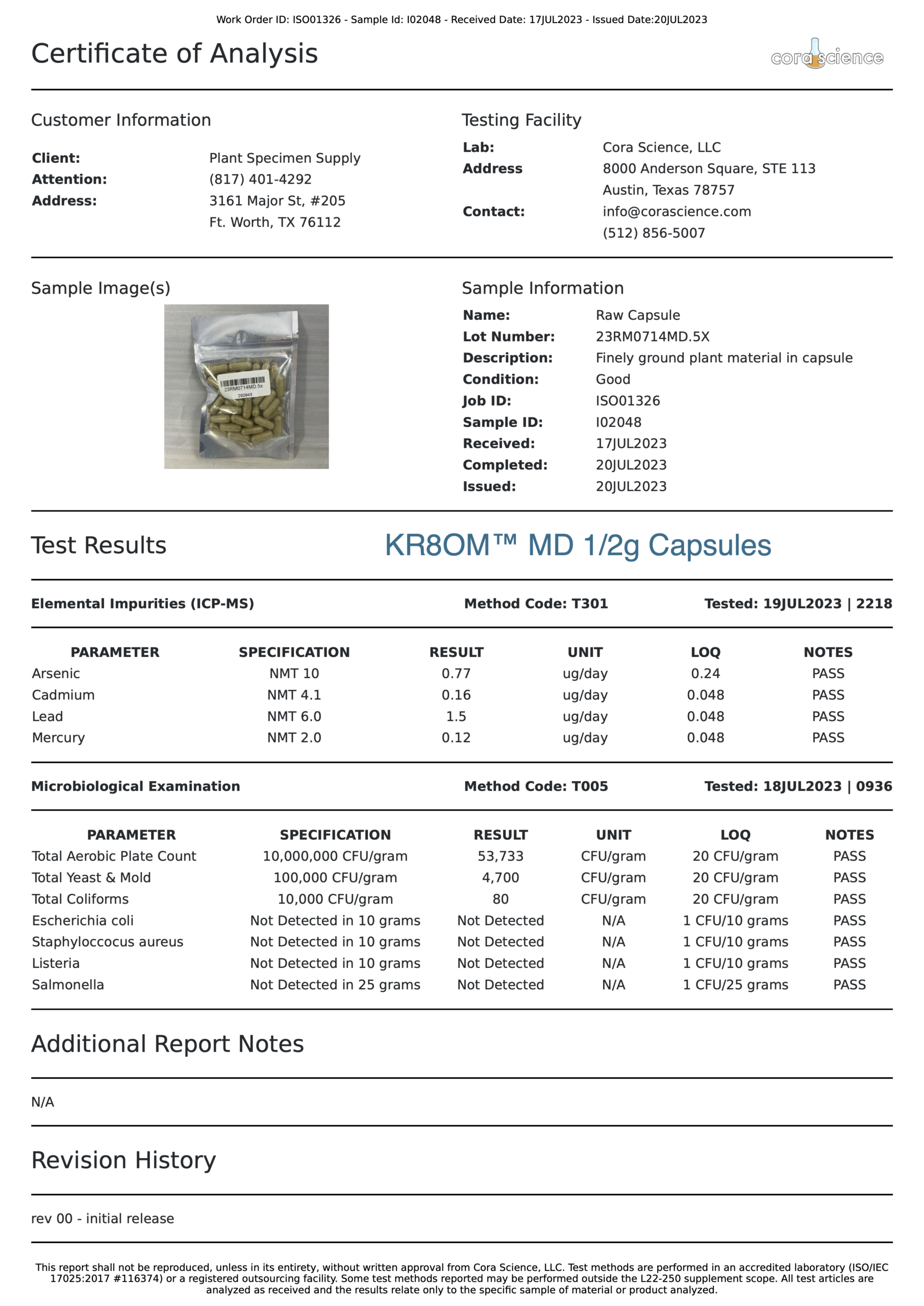

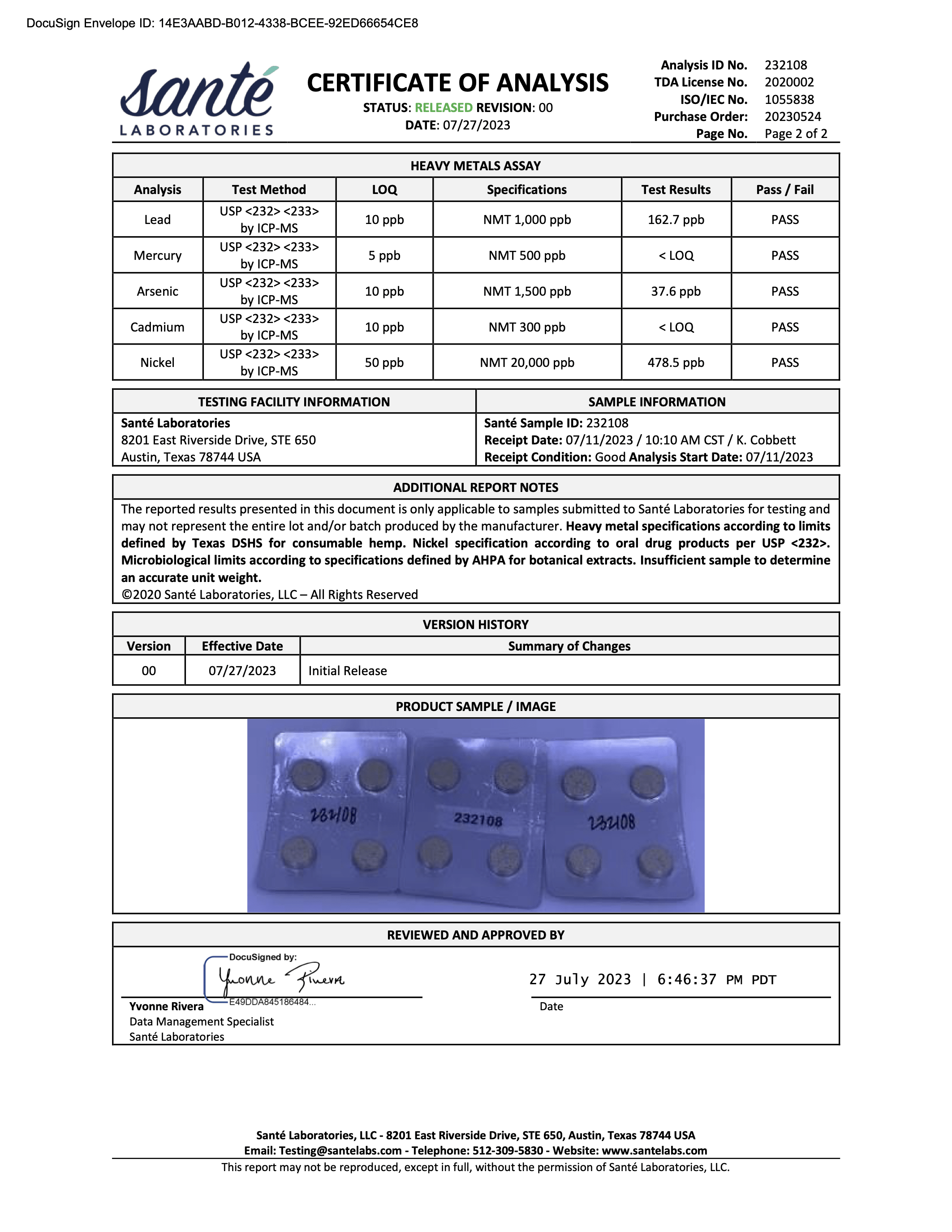

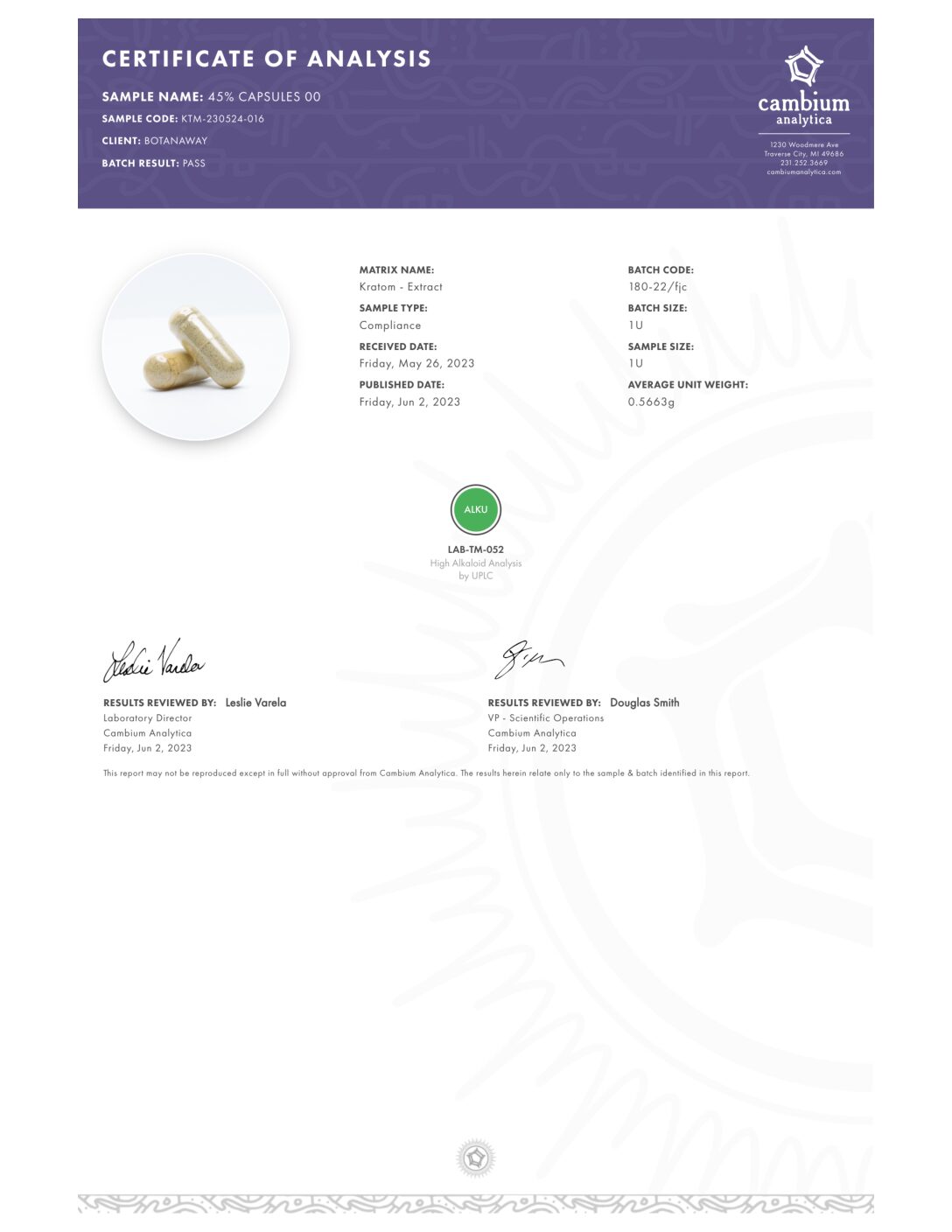

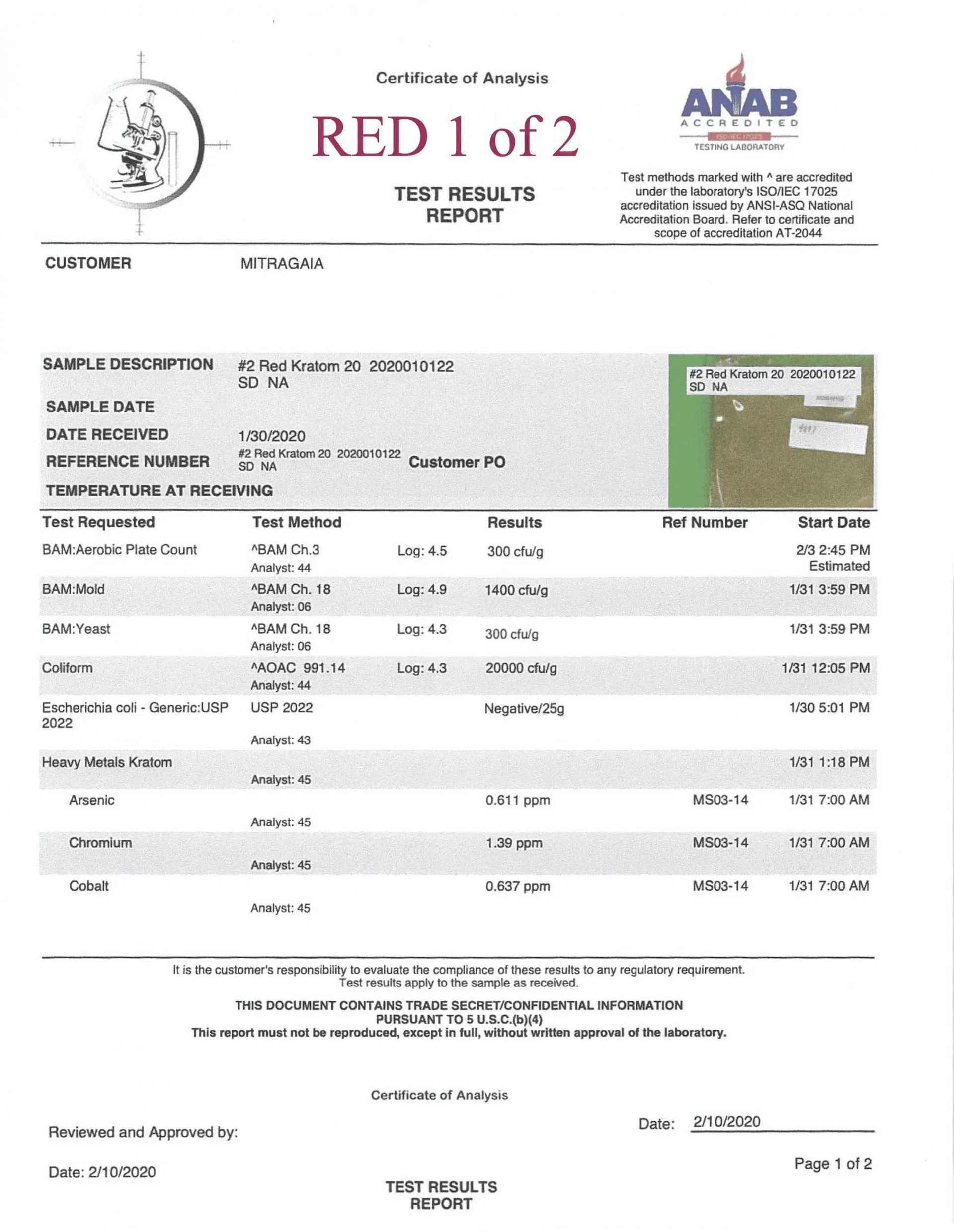

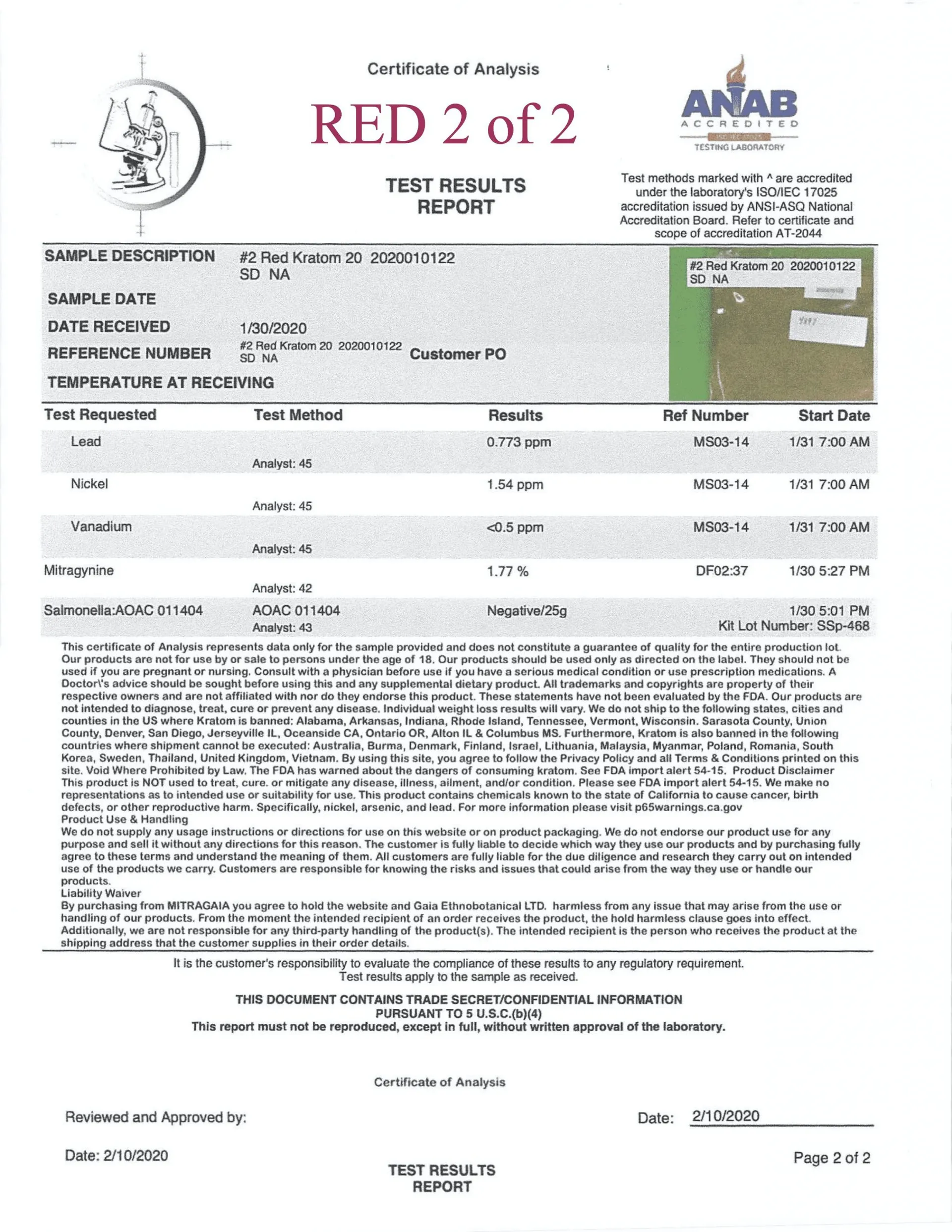

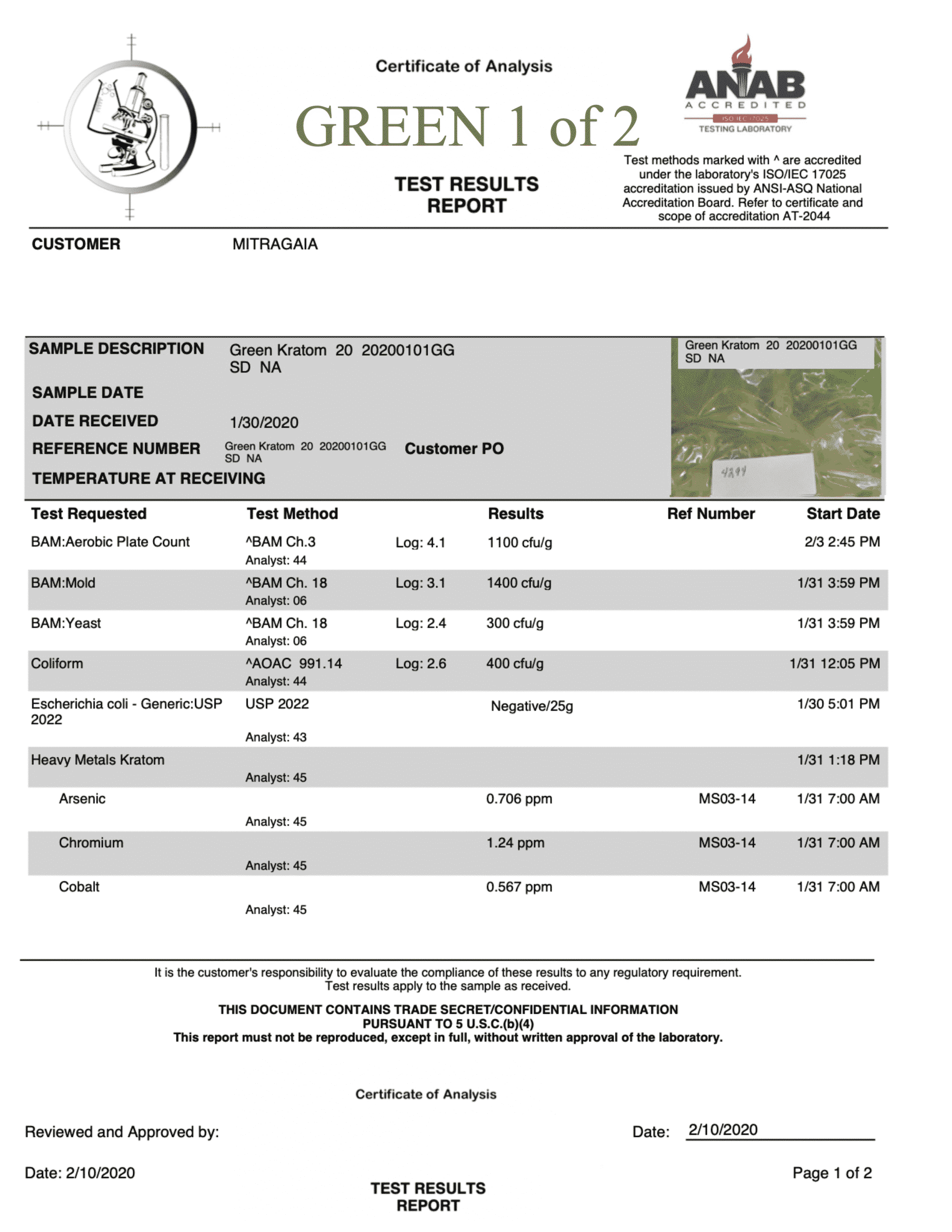

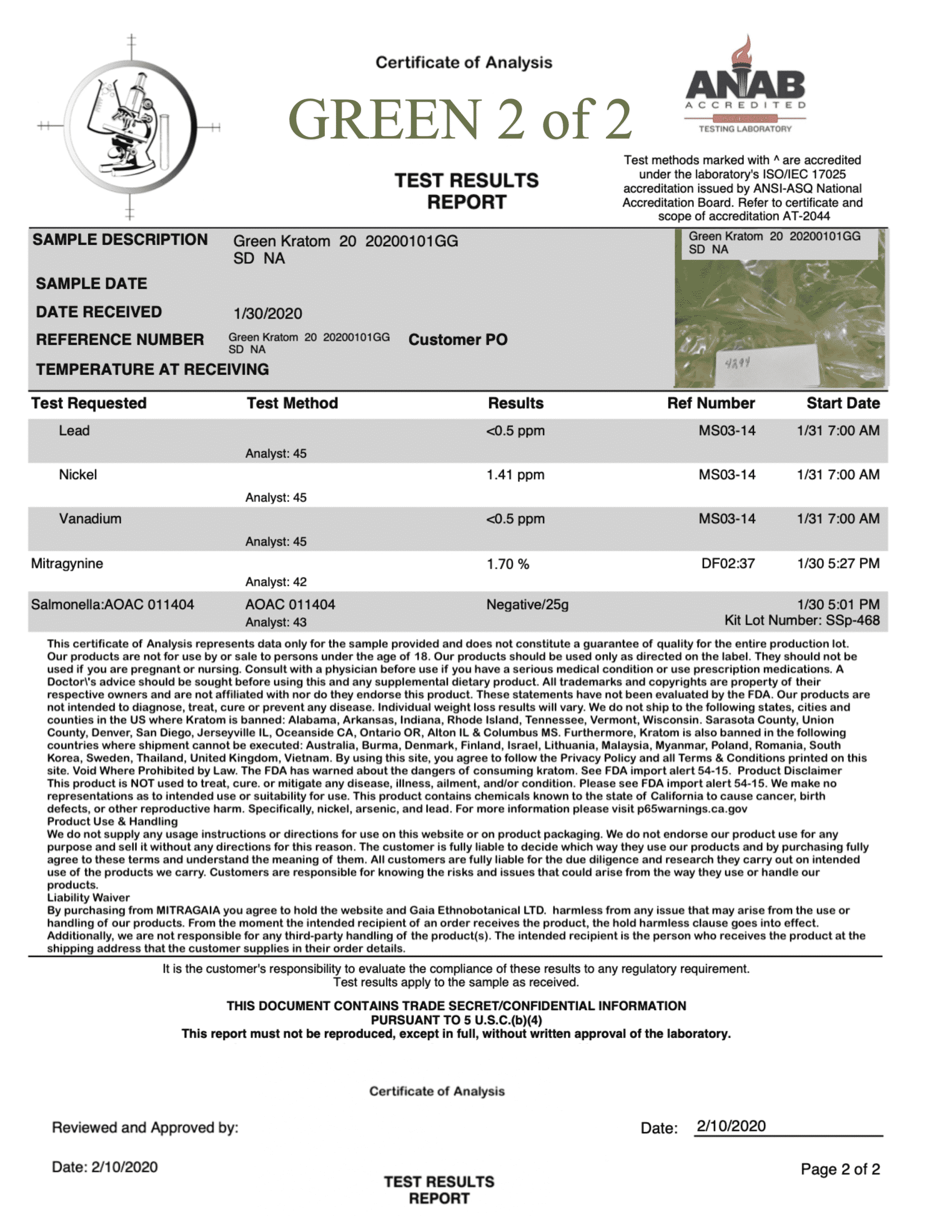

As with most products of similar characteristics and uses, it is critical to have the kratom tested for quality, alkaloid content, and more importantly, safety. With any all-natural product, there are many factors that can, directly and indirectly, attribute to quality such as growing conditions, harvesting practices, transportation, storage, and even packaging and handling practices. When the product is tested at our third-party ISO 17025 accredited laboratory you achieve more than just test results, you gain the confidence and peace of mind of knowing what you’re actually consuming. Follow the science and know what you’re buying.

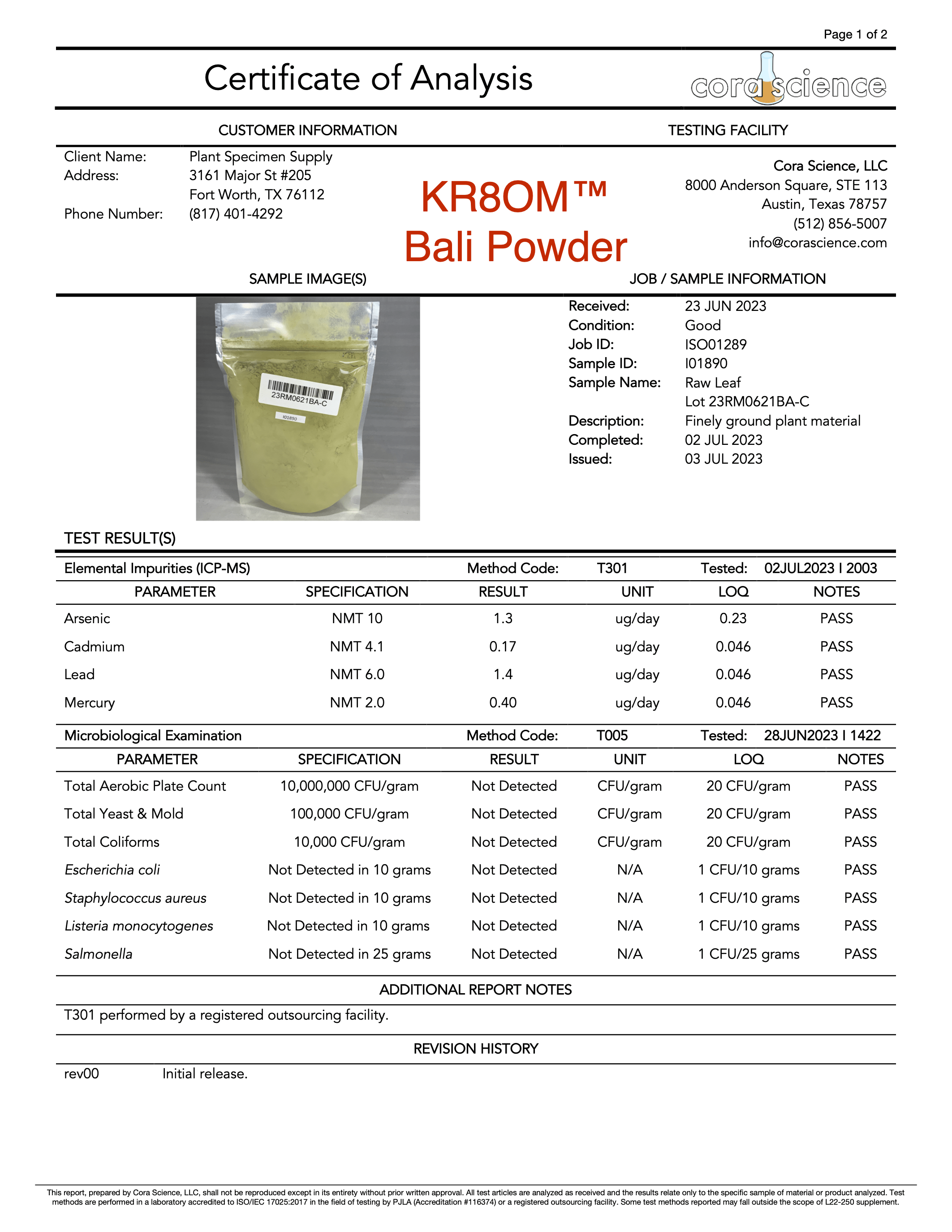

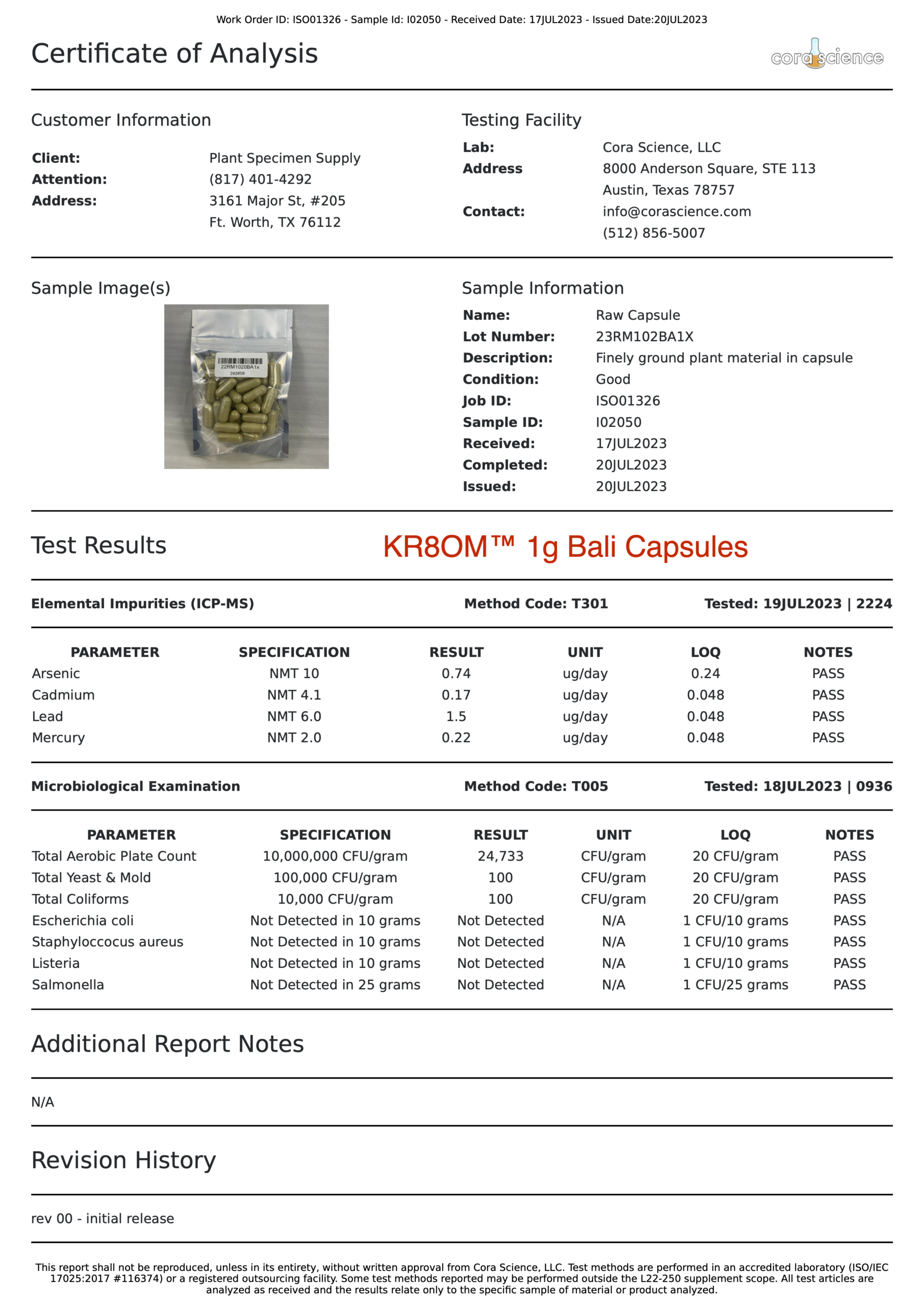

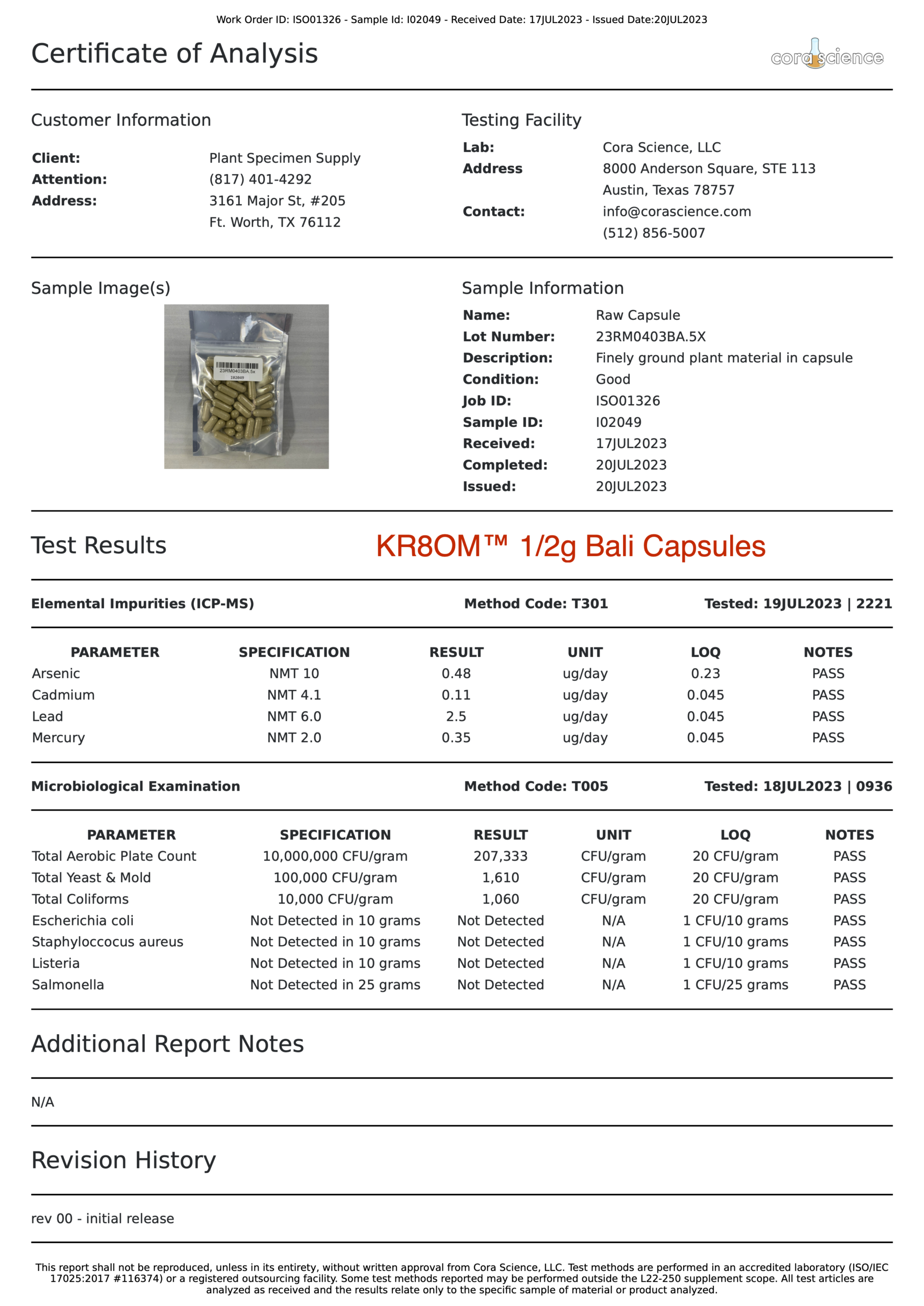

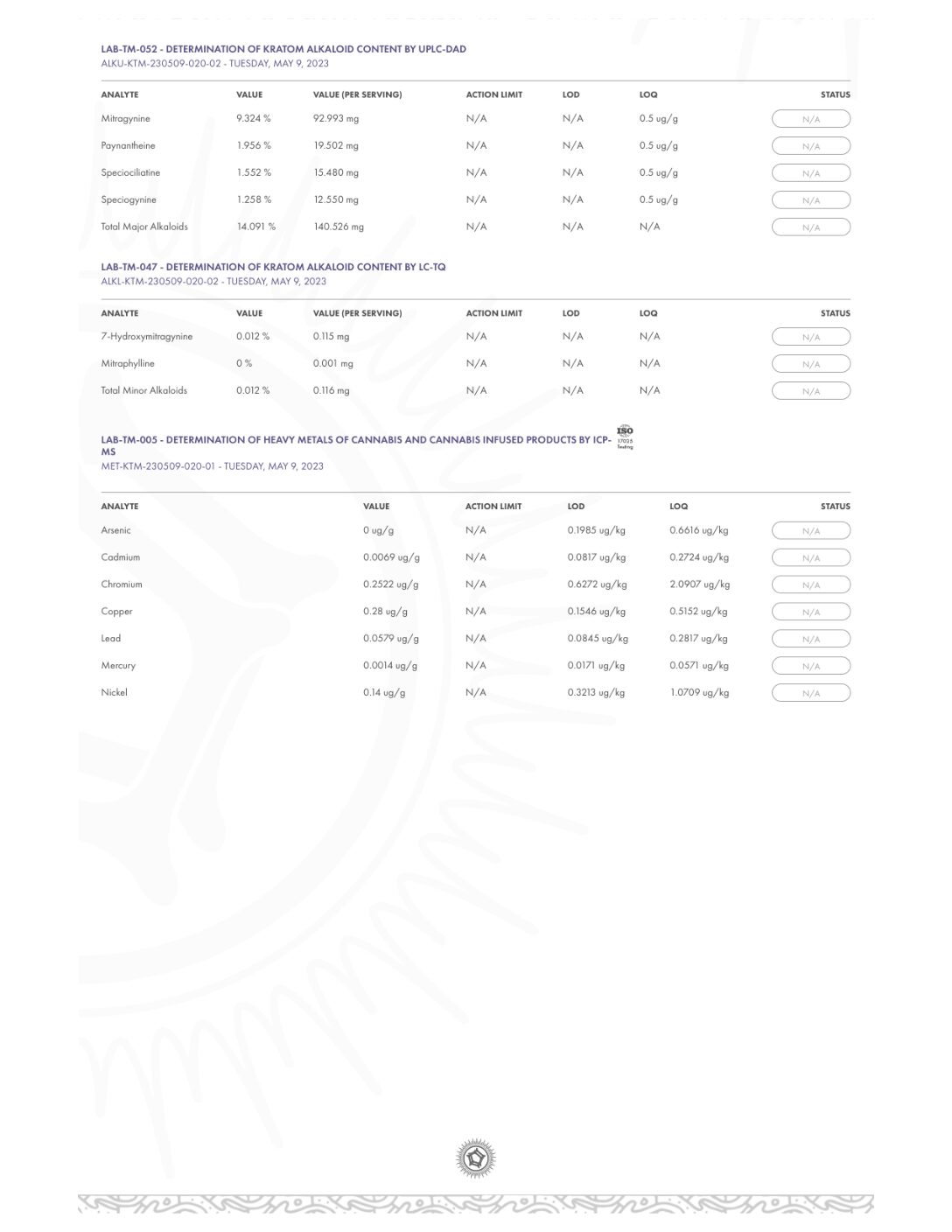

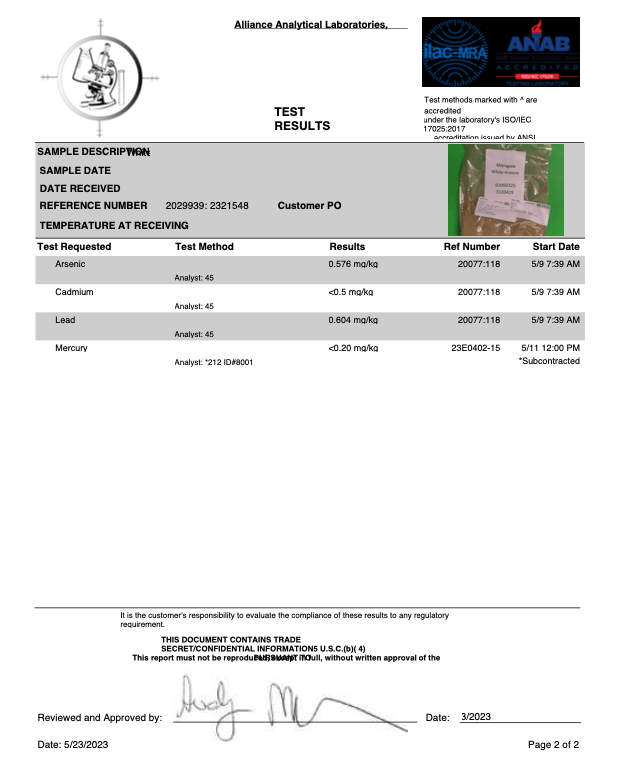

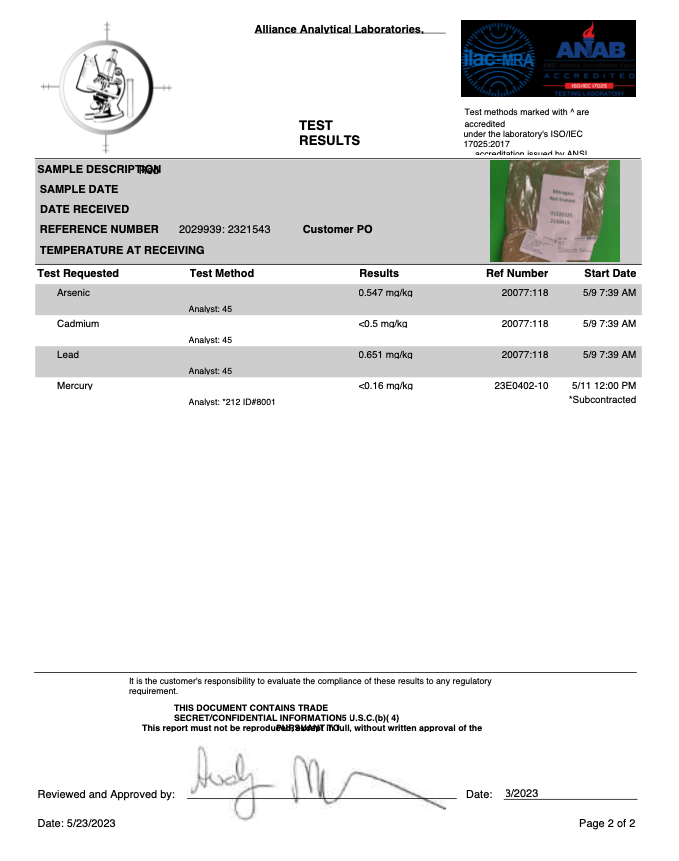

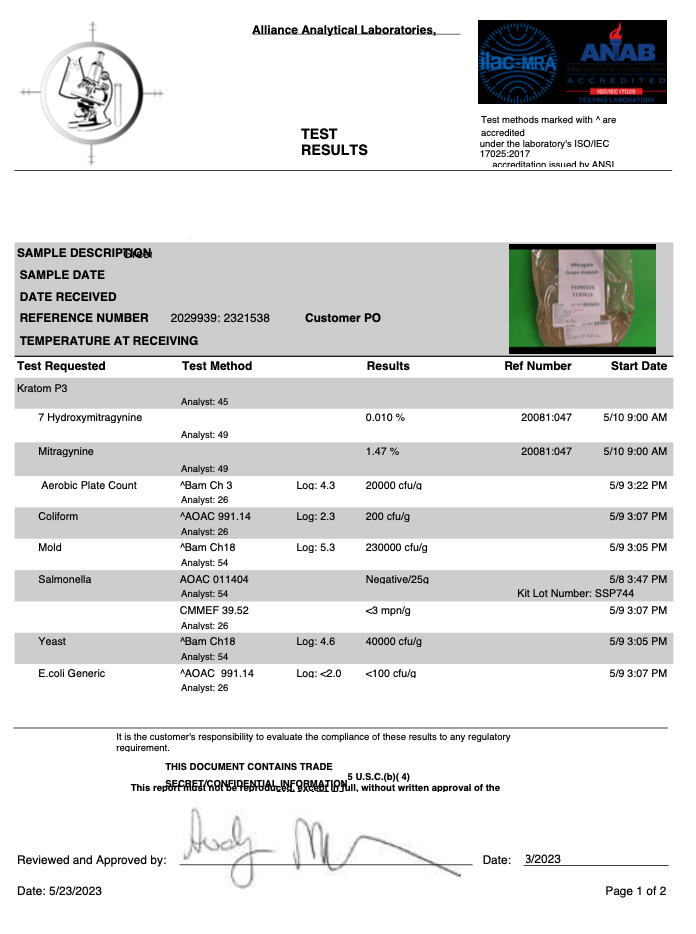

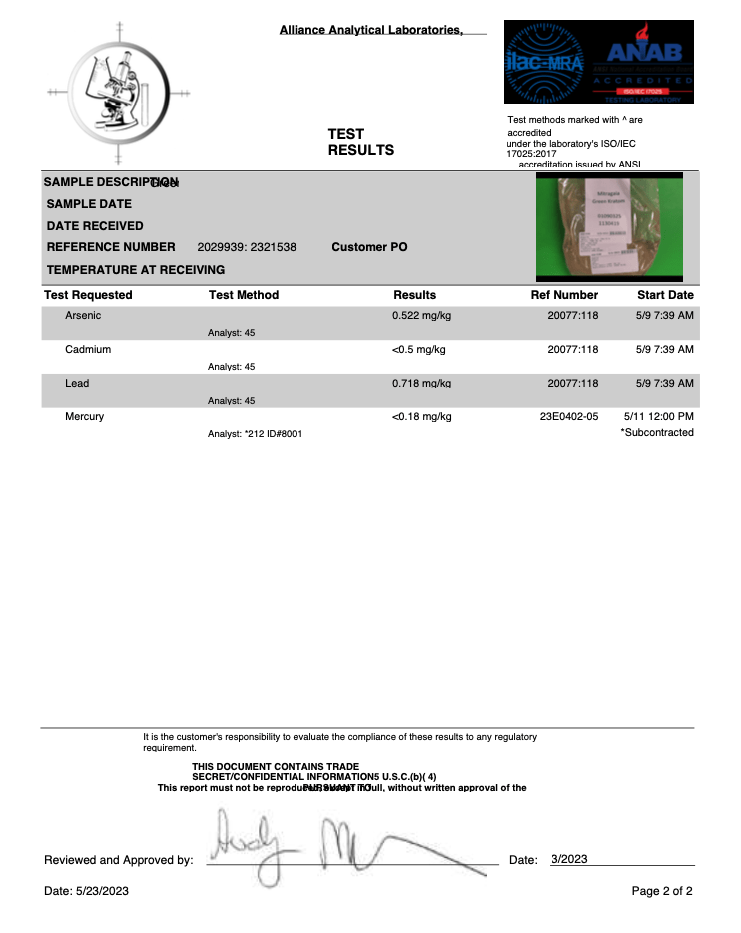

- Arsenic (As)

- Cadmium (Cd)

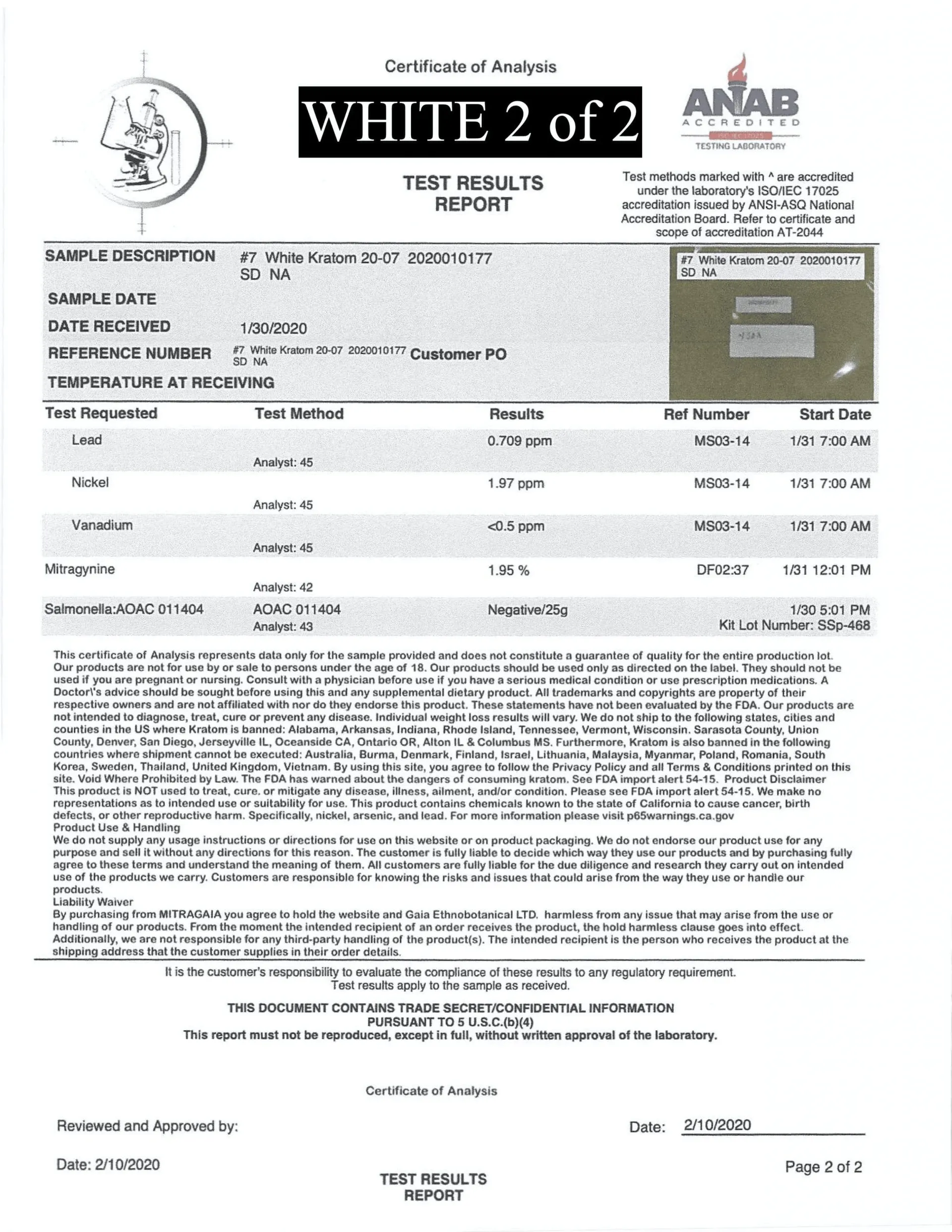

- Lead (Pb)

- Mercury (Hg)

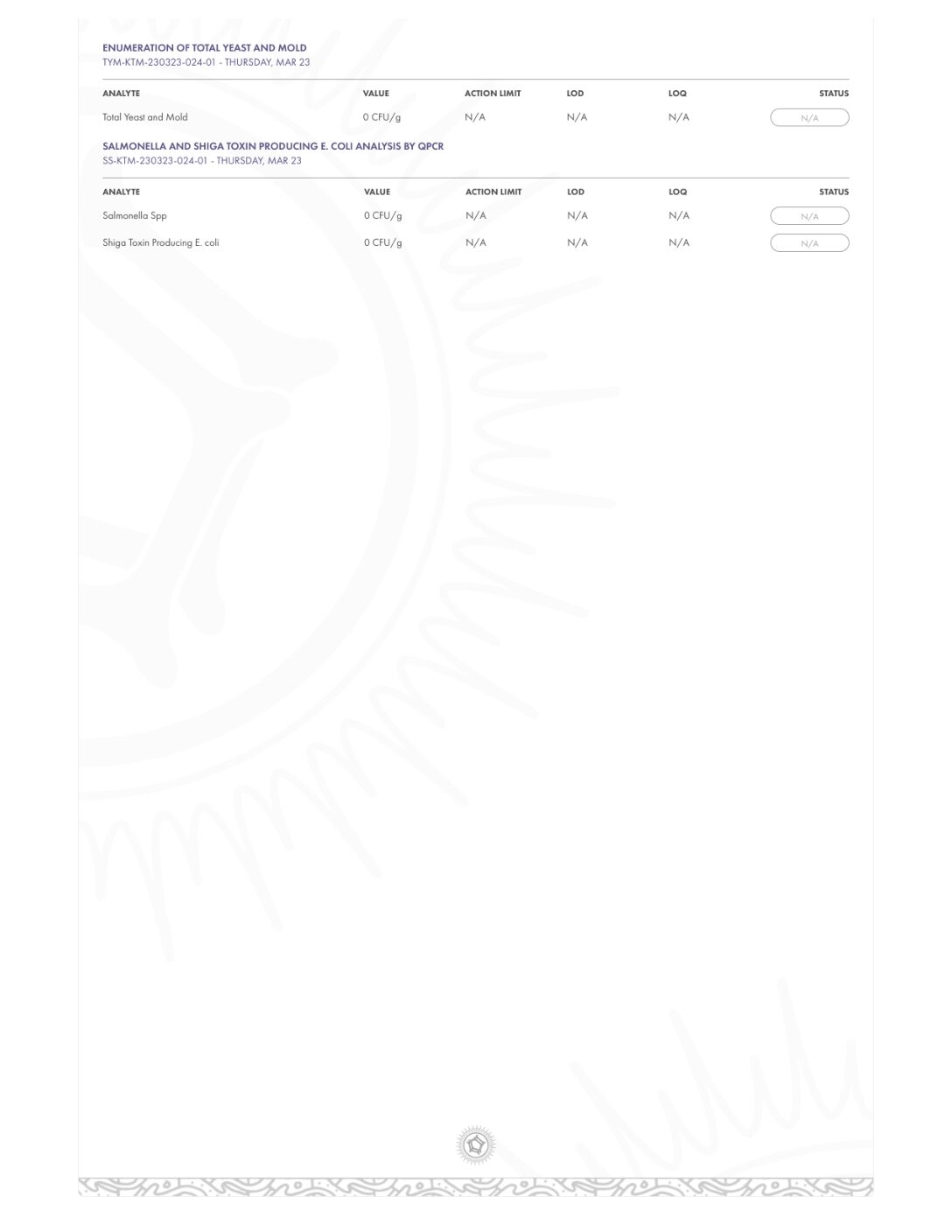

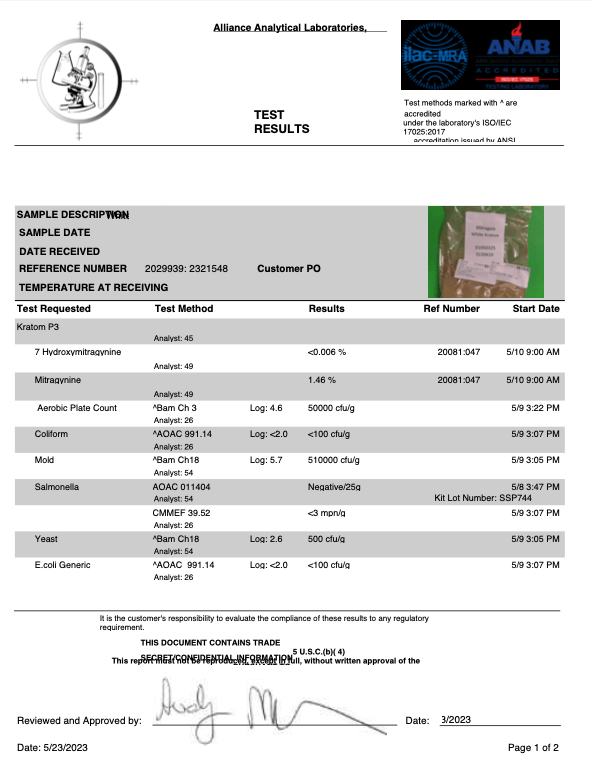

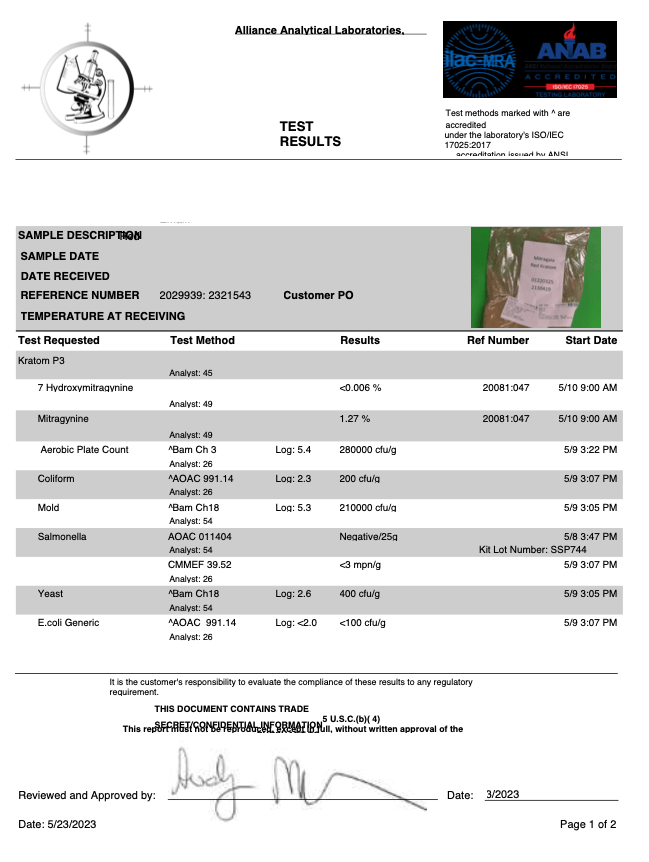

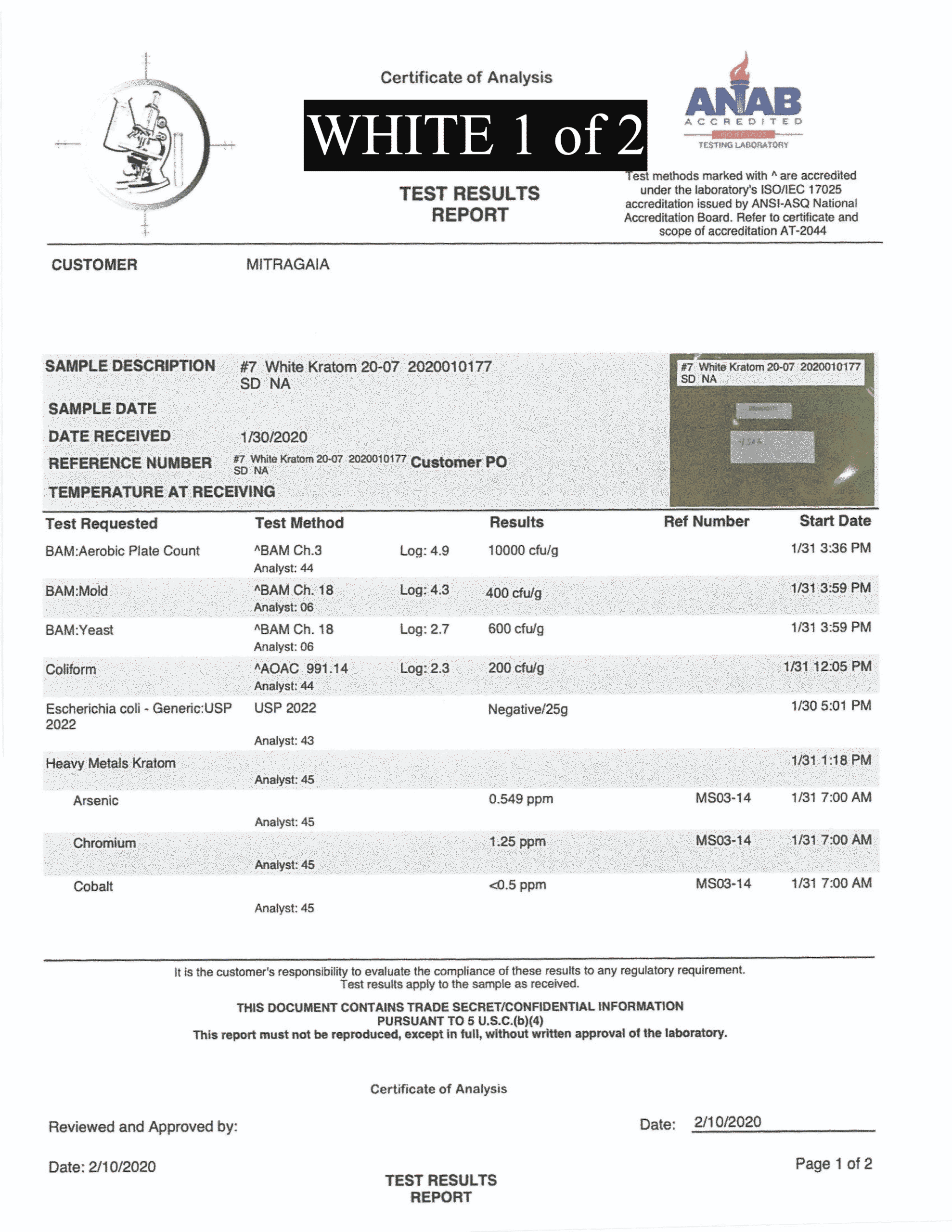

- Salmonella

- Escherichia coli (E. Coli)

- Shiga toxin-producing E.coli

- Escherichia coli

- Staphylococcus

- Listeria

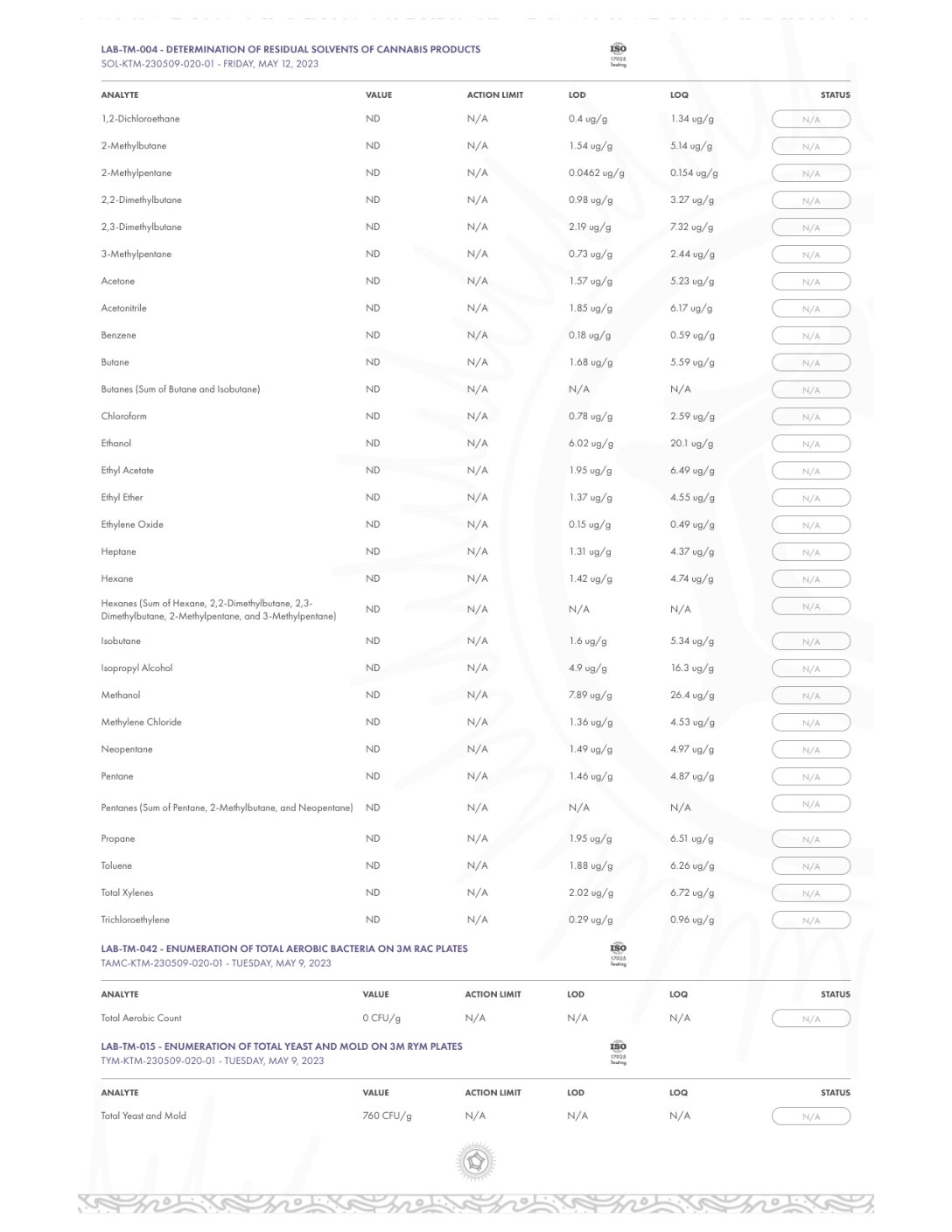

- Yeast

- Mold

- Aerobic Plate Counts

- stx and eae genes

- Heavy Metals

- Total Coliform Bacteria

- Staphylococcus sp.

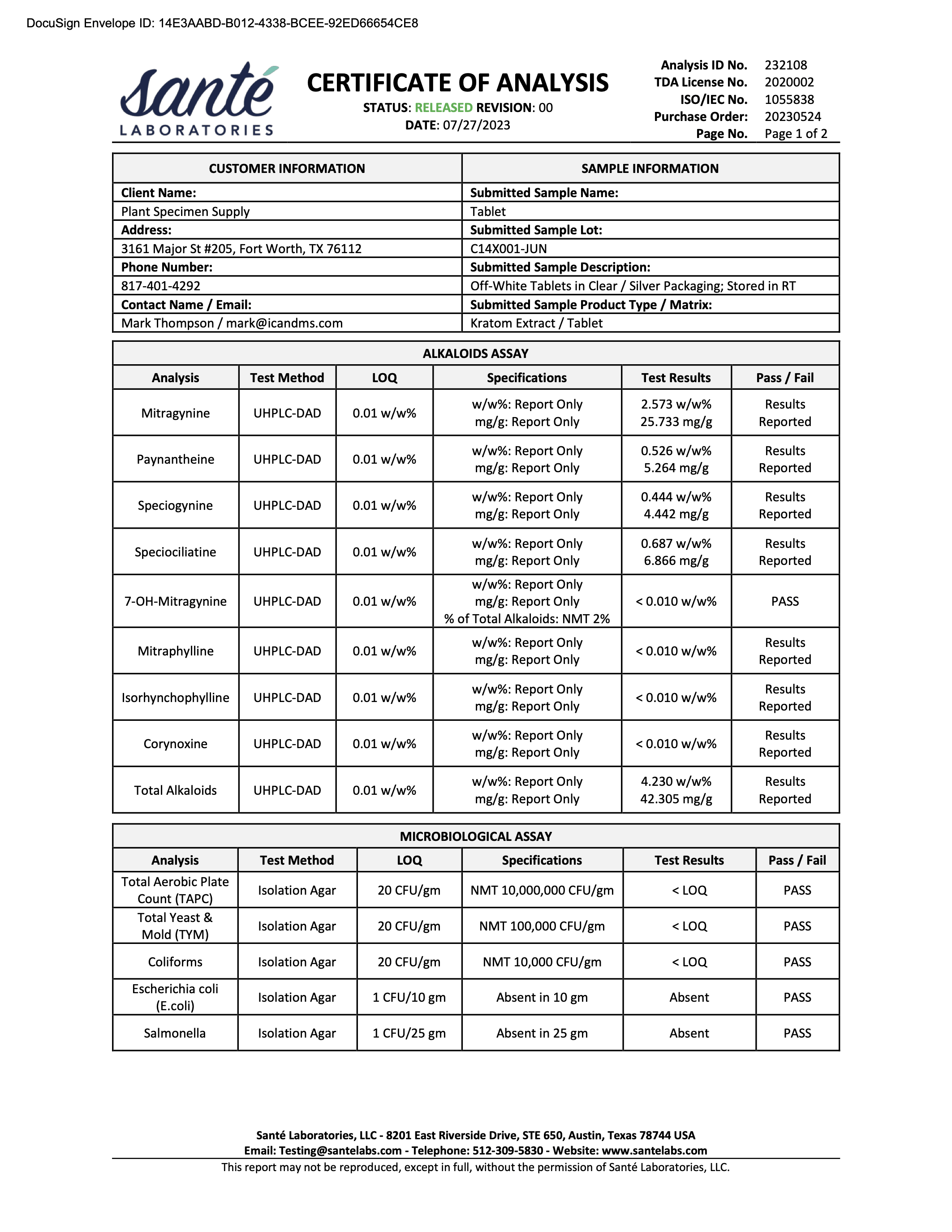

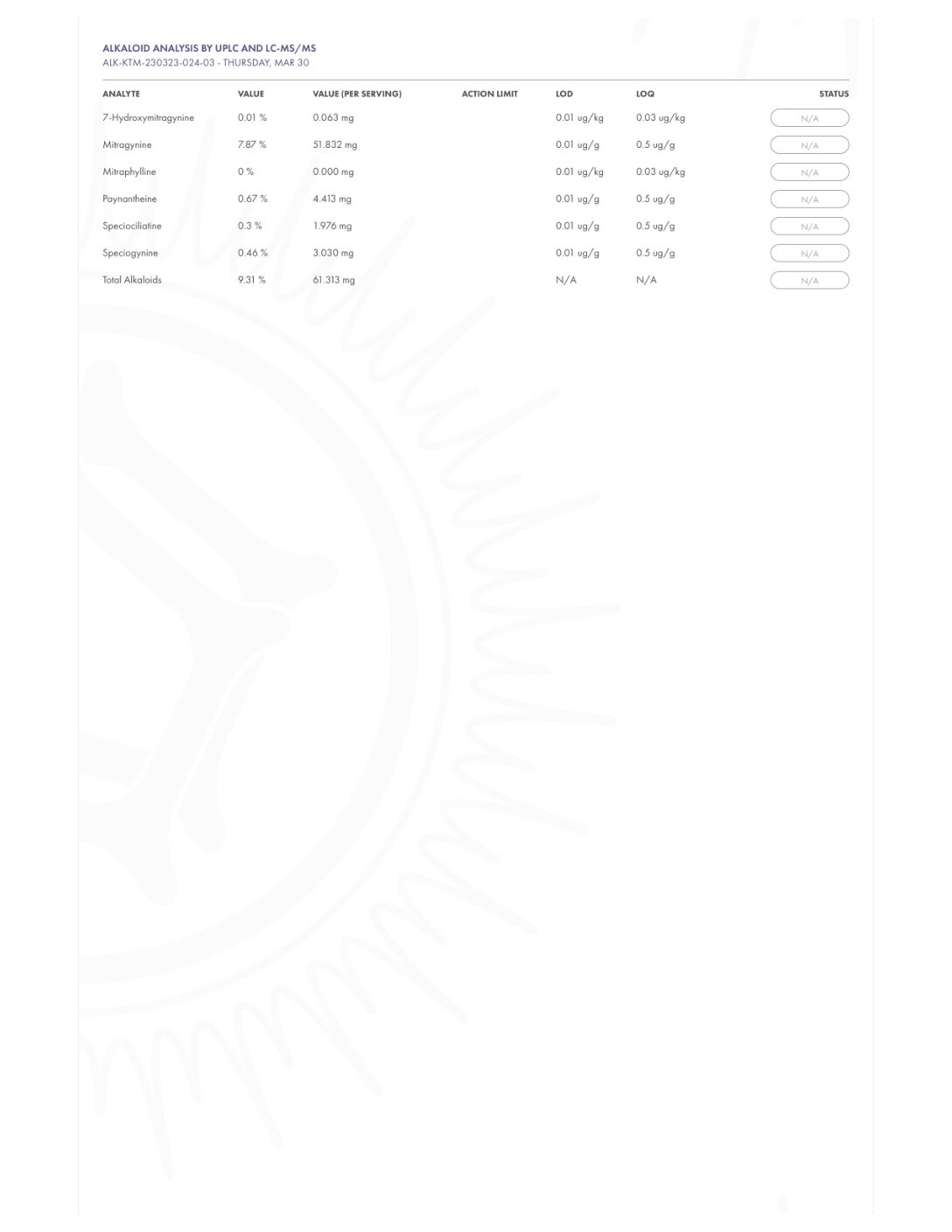

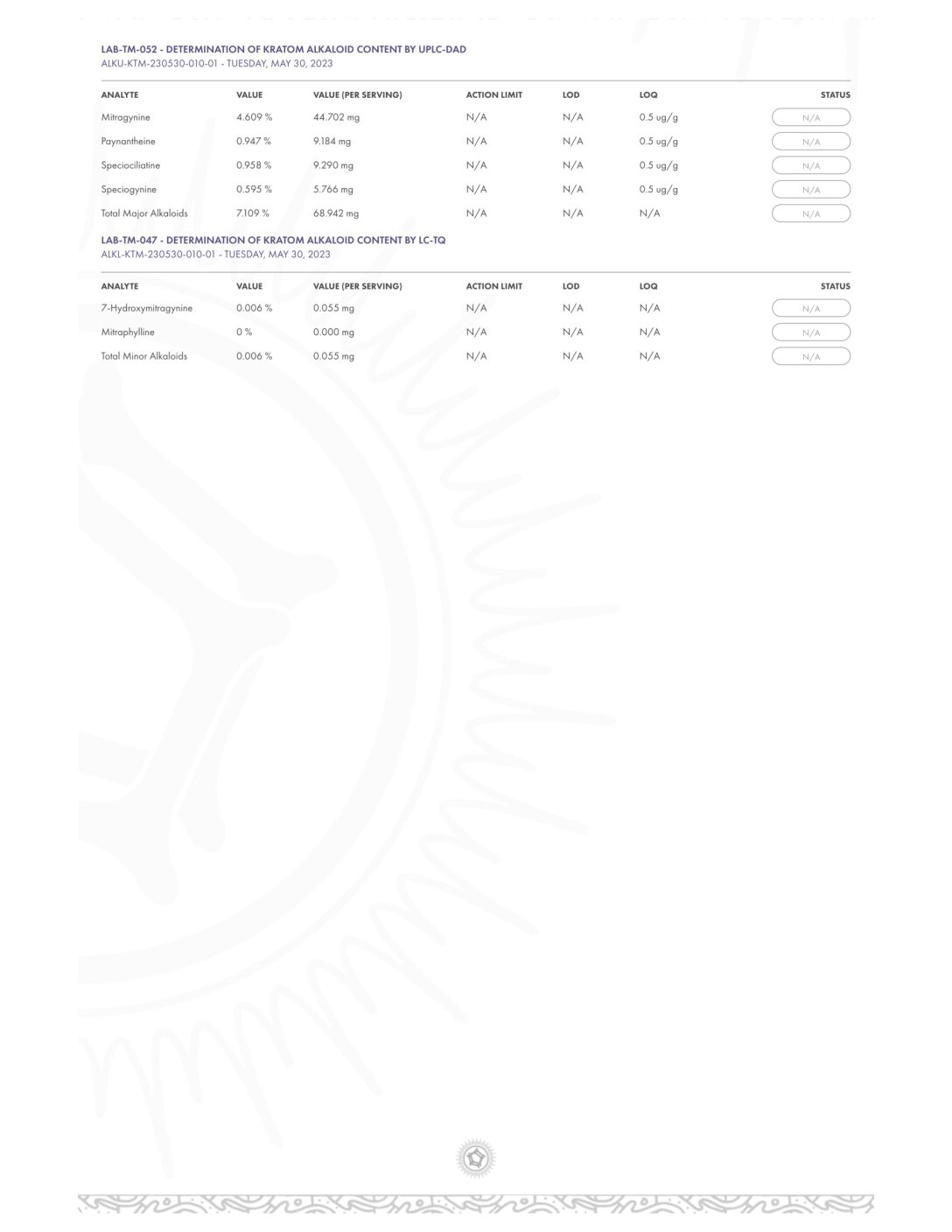

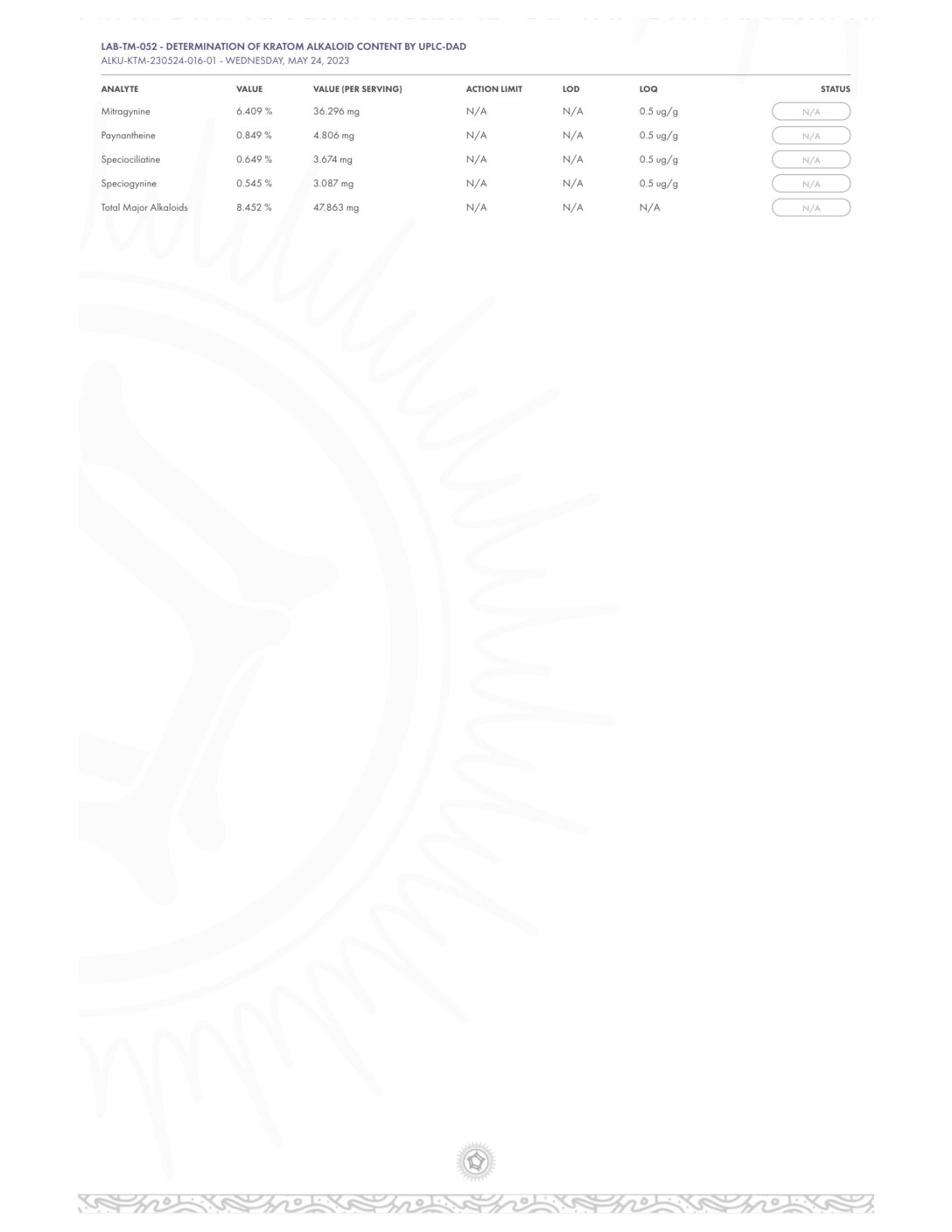

- Alkaloid Content

- Mitragynine

- 7-hydroxymitragynine

A compilation of material describing what bacteria the Aerobic Plate Count analysis detects and what the kratom lab test results mean.

The Aerobic Plate Count (APC) is used as an indicator of bacterial populations on a sample. It is also called the aerobic colony count, standard plate count, Mesophilic count or Total Plate Count.

The test is based on an assumption that each cell will form a visible colony when mixed with agar containing the appropriate nutrients. It is not a measure of the entire bacterial population; it is a generic test for organisms that grow aerobically at mesophilic temperatures (25 to 40°C; 77 to 104°F).

APC does not differentiate types of bacteria.

APC can be used to gauge sanitary quality, organoleptic acceptability, adherence to good manufacturing practices, and to a lesser extent, as an indicator of safety. APC may also provide information regarding shelf life or impending organoleptic change in a food.

APCs are poor indicators of safety in most instances, since they do not directly correlate to the presence of pathogens or toxins. A low APC result does not mean the product or ingredient is pathogen free. However, some products or ingredients showing excessively or unusually high APCs may reasonably be assumed to be potential health hazards, pending pathogen screening results. Interpretation of the APC results must take into consideration knowledge of the product and whether a high APC is expected.

Depending on the situation, APC can be valuable in evaluating food quality. Large numbers of bacteria may be an indication may be an indication of poor sanitation or problems with process control or ingredients. Certain products, such as those produced through fermentation, naturally have a high APC. Again, low APC numbers do not equate to an absence of pathogens. Often, it is necessary to assay foods for specific pathogens or spoilage organisms before ruling on food safety or food quality.

Quality and safety guidelines or specifications are often applied to raw materials and finished goods. Using APC for ingredients may or may not be appropriate as a quality indicator. A food manufacturer’s decision to apply APC guidelines on ingredients must be based on the ingredient’s effect on the finished product. For instance, in dried foods, APC can be used as a means of assessing the adequacy of moisture control during the drying process. For meats, APC can be used to check to the condition of incoming carcasses to potentially identify suppliers who prove those with excessively high counts. APC can also be used to evaluate sanitary conditions of equipment and utensils. This can be done during processing to monitor buildup and after sanitation to gauge its effectiveness.

The table below offers some general guidelines for expected aerobic plate counts on ingredients and finished products. Bear in mind, APC specifications are not always appropriate. For example, raw agricultural commodities can have widely fluctuating plate counts. In these situations, APC can provide meaningful data to the processor who has a better understanding of factors that may influence the count, but they provide little value in relation to acceptance criteria.

Table 1 Typical Commodity Aerobic Plate Counts (CFU/g)

|

Commodity |

Aerobic Plate Count per Gram |

Commodity |

Aerobic Plate Count per Gram |

|

Almonds |

3,000 – 7,000 |

Pasta |

1,000 – 10,000 |

|

Baked Goods |

10 – 1,000 |

Prepackaged Cut Chicken |

100,000 |

|

Breakfast Cereals |

0 – 100 |

Raw Milk |

800 – 630,000 |

|

Deli Salads |

10,000 – 100,000 |

Refrigerated and frozen dough |

100 – 1,000,000 |

|

Dry Cereal Mixes |

100 – 100,000 |

Soy Protein |

100 – 100,000 |

|

Fresh Ground Beef |

100,000 |

Walnuts |

31,000 – 2,000,000 |

|

Frozen Potatoes |

1,000 – 100,000 |

Wild Rice (before hulling) |

1,800,000 |

|

Frozen Vegetables |

1,000 – 100,000 |

Wild Rice (after hulling) |

1,400 |

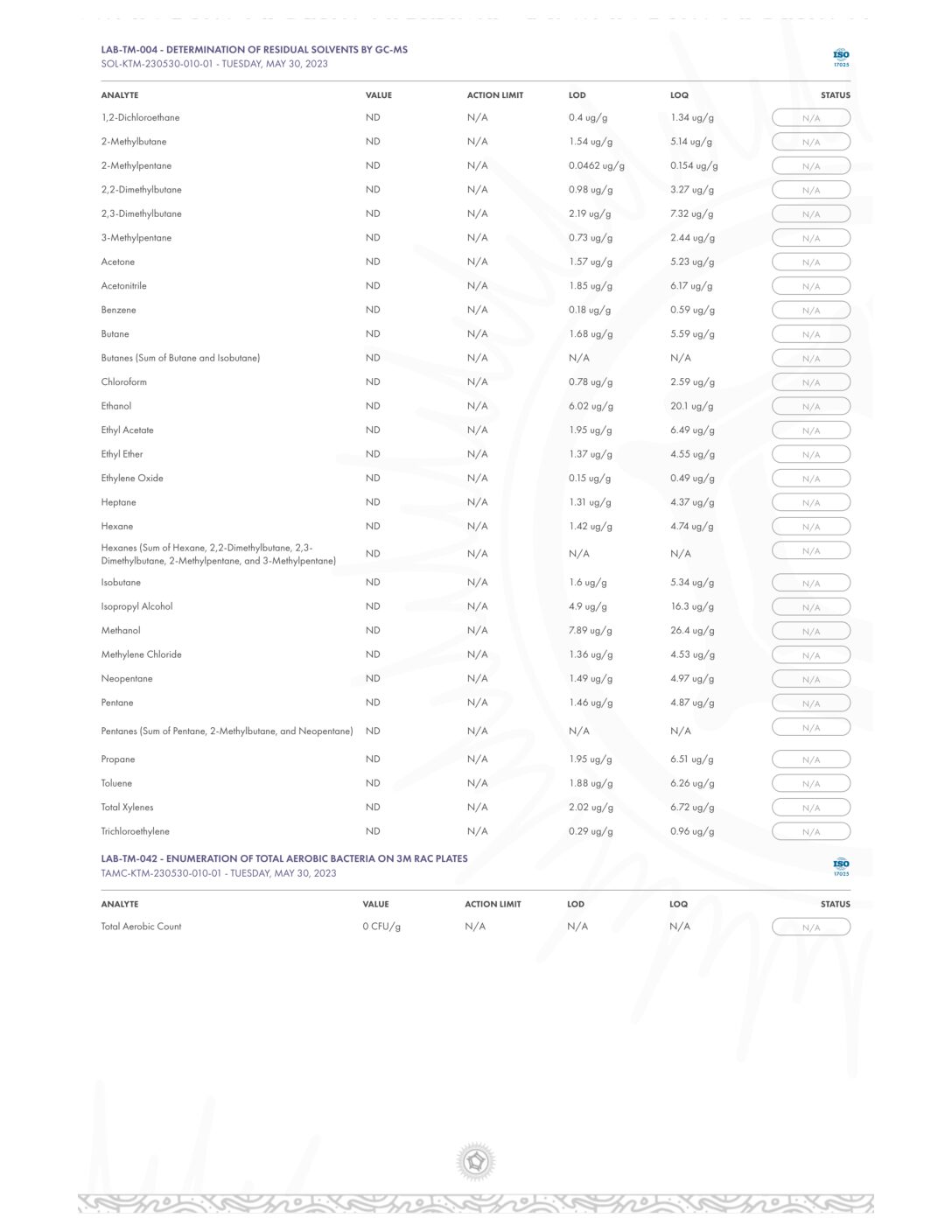

Pesticides via LCMS/MS

As one of the most widely used products across the world pesticides are an effective substance to control pests that may be harmful to cultivated plants. Due to the extremely common practice of using pesticides people can be exposed to low levels and as such suffer from a large range of risks between minor irritation to compromising the nervous system. The EPA has set their own policies that dictate the Maximum Residue Limits (MRL) and Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) in products and these regulations are in place to protect the public and the environment. Testing is very important in order to provide accurate and defensible data that ensures a toxin free product.

Complete Analyte List, Detection Limit 0.010 µg/g (ppm)

|

• Abamectin •Acephate •Acequinocyl •Acetamiprid •Aldicarb •Azoxystrobin •Bifenazate •Bifenthrin •Boscalid •Carbaryl •Carbofuran •Chlorantraniliprole •Chlorfenapyr •Chlorpyrifos •Coumaphos •Clofentezine •Cyfluthrin •Cypermethrin •Daminozide •DDVP (Dichlorvos) |

• Diazinon •Dimethoate •Dimethomorph •Ethoprop(hos) •Etofenprox •Etoxazole •Fenoxycarb •Fenhexamid •Fenpyroximate •Fipronil •Flonicamid •Fludioxonil •Hexythiazox •Imazalil •Imidacloprid •Kresoxim-methyl •Malathion •Methiocarb •Metalaxyl •Methomyl •Mevinphos |

• Myclobutanil •Oxamyl •Paclobutrazol •Permethrin •Phosmet •Piperonylbutoxide •Prallethrin •Propiconazole •Propoxur •Pyrethrins •Pyridaben •Spinetoram •Spinosad •Spiromesifen •Spirotetramat •Spiroxamine •Tebuconazole •Thiacloprid •Thiamethoxam •Trifloxystrobin |

A compilation describing coliforms, Enterobacteriaceae, and E. coli and their role as indicator organisms of possible pathogen contamination.

Three groups of microorganisms are commonly tested for and used as indicators of overall food quality and the hygienic conditions present during food processing, and, to a lesser extent, as a marker or index of the potential presence of pathogens (i.e. food safety): coliforms, Escherichia coli (E. coli; also a coliform) and Enterobacteriaceae.

Index Microorganisms

Microbiological criteria for food safety which defines an appropriately selected microorganism as an index microorganisms suggest the possibility of a microbial hazard without actually testing for specific pathogens. Index organisms signal the increased likelihood of a pathogen originating from the same source as the index organism and thus serve a predictive function. Higher levels of index organisms may (in certain circumstances), correlate with a greater probability of an enteric pathogen(s) being present. The absence of the index organism does not always mean that the food is free from enteric pathogens.

Indicator Microorganisms

The presence of indicator microorganisms in foods can be used to: assess the adequacy of a heating process designed to inactivate vegetative bacteria, therefore indicating process failure or success; assess the hygienic status of the production environment and processing conditions; assess the risk of post-processing contamination; assess the overall quality of the food product.

A number of factors must be considered before testing for a particular indicator organism or group of organisms: the physio-chemical nature of the food; the native microflora of the food (fresh fruit and vegetables often carry high levels of Enterobacteriaceae and/or coliforms as part of their normal flora); the extent to which the food has been processed; the effect that processing would be expected to have on the indicator organism(s); the physiology of the indicator organism(s); the physiology of the indicator organism(s) chosen.

Enterobacteriaceae

The taxonomically defined family, Enterobacteriaceae, includes those facultatively anaerobic gram-negative straight bacilli which ferment glucose to acid, are oxidase-negative, usually catalase-positive, usually nitrate-reducing, and motile by peritrichous flagella or nonmotile.

The Enterobacteriaceae group does include many coliforms, with the addition of other microorganisms which ferment glucose instead of lactose (i.e. Salmonella). Common foodborne genera of the Family Enterobacteriaceae include Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Erwinia, Escherichia, Hafnia, Klebsiella, Proteus, Providencia, Salmonella, Serratia, Shigella, and Yersinia. Psychrotrophic strains of Enterobacter, Hafnia, and Serratia may grow at temperatures as low as 0C.

If the meat ecosystem favors their growth, genera in the family Enterobacteriaceae may be important in muscle food spoilage. Conditions allowing growth of Enterobacteriaceae include limited oxygen and low temperature. Members of this family produce ammonia and volatile sulfides, including hydrogen sulfide and malodorous amines, from amino acid metabolism.

The Enterobacteriaceae have been used for years in Europe as indicators of food quality and indices of food safety. The use of coliforms as indicators of food quality or insanitation in food processing environments is based upon tradition in the United States. This practice arbitrarily bases judgment on food quality or manufacturing plant insanitation upon recovery of those members of the Enterobacteriaceae group (i.e. coliforms) which ferment lactose, thus ignoring the presence of non-lactose fermenting members.

E. coli

A gram negative rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms (endotherms). Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some, such as serotype O157:H7 can cause serious food poisoning in humans. The harmless strains are part of the normal flora of the gut, and can benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K, and by preventing the establishment of pathogenic bacteria within the intestine. E. coli are easily destroyed be heat, and cell numbers may decline during freezing and frozen storage of foods.

E. coli is the only member of the coliform group that unquestionably is an inhabitant of the intestinal tract and it has become the definitive organism for the demonstration of fecal pollution of water and food not undergoing any processing which would kill the organism.

In cases where it is desirable to determine whether fecal contamination may have occurred, at present, E. coli is the most widely used indicator of such, the presence of which implies a risk that other enteric pathogens may be present in the food. In many raw foods of animal origin, small number of E. coli can be expected because of the close association of these foods with the animal environment and the likelihood of contamination of carcasses from fecal material, hides, or feathers during slaughter-dressing procedures. The failure to detect E. coli in a food, however, does not assure the absence of enteric pathogens.

However, criteria involving E. coli are generally not useful for detecting likely fecal contamination for foods that have been processed sufficiently to destroy this bacterium.

E. coli are not always confined to the intestine; they have the ability to survive in the food processing plant environment and re-contaminate processed foods (E. coli found in environmental swabs is a good indication of fecal contamination). Hence, the presence of E. coli in a heat-processed food does not necessarily indicate fecal contamination, but indicates either process failure or, more commonly, post-processing contamination from equipment or employees or from contact with contaminated raw foods.

Dairy microbiologists use E .coli as a true indicator organism to assess post-pasteurization contamination in milk. The presence of E. coli in pasteurized milk may indicate inadequate pasteurization, poor hygienic conditions in the processing plant, and/or post-processing contamination because proper pasteurization inactivates levels of E. coli anticipated in raw milk.

Coliform

The coliform group is defined on the basis of biochemical reactions, not genetic relationships, and thus the term “coliform” has no taxonomic validity. Coliforms are aerobic and facultatively anaerobic, gram negative, non-sporeforming rods that ferment lactose, forming acid and gas within 48 hours at 35C.

In the case of refrigerated ready-to-eat products, coliforms are recommended as indicators of process integrity with regard to reintroduction of pathogens from environmental sources and maintenance of adequate refrigeration. The source of coliforms in these types of products after thermal processing is usually the processing environment, resulting from inadequate sanitation procedures and/or temperature control.

Coliforms are ubiquitous in nature, therefore a number of factors should be considered when testing for a particular indicator organism such as the native microflora of the food, the extent to which the food has been processed, and the effect that processing would be expected to have on the indicator organisms.